Suan Mokkh: The Garden of Liberation

Suan Mokkh is a forest monastery along the coast of Southern Thailand, 600 km from Bangkok. It was founded in 1932 by Buddhadāsa Bhikkhu and grew to become the most innovative and progressive Buddhist teaching center in Siam. Although Buddhadāsa Bhikkhu has passed away, much of his work continues. This site is a continuation of that work, one of many virtual Suan Mokkhs. As the true Suan Mokkh can only be found within the nature of the silent mind, any attempt to speak of it is virtual, whether in talks, books, or cyberspace. Here we attempt to extend the discoveries of Suan Mokkh into the 84,000 virtual worlds. May the contents support you in the realization of the liberation that is ever now within the nature of the mind that is experiencing this “reality,” virtual or what-have-you.

The Suan Mokkh of Buddhadāsa Bhikkhu may be difficult to find in some of the activities being carried out these days in his name. This should not discourage those who sincerely seek what he sought & taught: the end of suffering through not attaching to anything as “I” or “mine.” To the degree we can put this into practice, we will understand & discover “The Garden of Liberation” for ourselves, both within us and as we help reveal it in whatever place we find ourselves. It isn't necessary to seek Suan Mokkh in the place where Buddhadāsa Bhikkhu once lived. Seek it wherever you are!

INTRODUCTION

This article was written by Santikaro Bhikkhu in 1988, for Monastic Studies, a Catholic journal. Since then, Ajahn Buddhadāsa has died & others have taken over leadership of the monastery he founded in 1932. There are some new directions, and the style is somewhat different, though it is still a fine place where many come to learn about & practice the Dhamma. Closer to mainstream Thai Buddhism than in the past, and with less attention to Ajahn Buddhadāsa's reformist legacy, the ideals described below nonetheless still are valid & continue to motivate those who seek liberation through non-attachment to "I" and "mine."

Suan Mokkh is located near the bulge on the upper Malay Peninsula that is the heart of Southern Thailand. The Gulf of Siam is not far away. From the red sandstone cliffs of Nang E Hill at the back of the Wat, the ocean and its tourist-catering islands are easily visible beyond a swamp, rice fields, and coconut palm groves. When the wind is right, the ocean breezes cool us; sometimes they sweep dark rain clouds down upon us. The Asia Highway runs past our door, north to Bangkok and south to Singapore. Houses spread up and down along it, forming a loose village most of which grew up after the Wat. All around are small rubber plantings, the dominant economic activity in the area. Suan Mokkh moved here around 1940 after its first site was outgrown. Two kilometers across the highway, screened by two limestone hills, forty acres of coconut groves are being developed into an international retreat center. The main site, less land given for a school and a Boy Scout camp, covers 120 acres.

A Wat is a residence for bhikkhus. Bhikkhus are men who have left home to take up the religious life within the teaching and training of the Lord Buddha2 Our Wat, centered on Golden Buddha Hill, is officially known as “Wat Tarn Nam Lai,” named after the “flowing stream” that runs down from Nang E Hill, which existed before Suan Mokkh came. The name Suan Mokkh can apply to the physical place also, and that is how most people understand it. Properly, it refers more to a place or state of mind that has realized the spiritual goal. The full name is Suan Mokkhabālārama, meaning “The Grove of the Powers of Liberation,” which points to the heart of spiritual inquiry and practice: liberation from ignorance, selfishness, and misery. Buddhadāsa Bhikkhu founded Suan Mokkh with the help of his younger brother and some of their friends in 1932 at a site about eight kilometers from here.3 He continues to head the community at the age of 85. Although much of Suan Mokkh's importance and uniqueness is due to the talents, inspiration, and controversy of its founder, this article will focus more on the community and the place itself.

My understanding of Buddhism and Suan Mokkh is far from complete. I am just beginning to fathom the things I try to describe here. I have lived here only three and a half years and do not have direct experience of its early years. Further, I am a farang (foreigner of European descent). Although I came here after four years of service in the U.S. Peace Corps, which gave me a good start toward comprehending Thai language and culture, as well as time to adjust to subtropical weather and painfully spicy food, a farang never completely blends into Thai contexts. My perspectives and appraisals are likely to differ from those of my Thai Dhamma comrades, especially those of older generations.

THE MONASTERY AND NATURE

The Buddha taught about Dhamma, rather than gods or a God.4 He didn't describe the Supreme Thing, ultimate truth, the fundamental nature of everything, or whatever we might call it, in personal or anthropomorphic terms. Dhamma is an ancient Indian word of great importance and vitality still. The meanings of this word Dhamma are rich and many. For a start, Suan Mokkh emphasizes four primary meanings:

• Nature (all reality and all things)

• Natural law (the law of conditionality, everything happens dependent on causes and conditions)

• Duty according to natural law (the duty of human beings at every step, stage, and moment of their living)

• Fruit from that duty (practiced in line with natural law).

If we wish, we can say also that Dhamma is the “Buddhist God,” a non-personal god, neither mind nor body, is Truth, is The Law. A Buddha merely discovers the Dhamma, nothing can create or effect it. Through a thorough understanding of Dhamma, the Buddha came to the realization that is the highest potential of humanity, the fruit of duty done perfectly — that is, selflessly — the end of all misery and suffering. He then honored and worshipped only this Dhamma. Those who follow the Buddha's path must do their best to penetrate through their own experience to the heart of Dhamma. A good way to begin is to live close to nature.

Strictly speaking, everything is natural, is part of nature. But somehow the naturalness of asphalt, concrete, polyester, and air-conditioning do not awaken the heart in the same way that trees, termites, rain clouds, and mud can. If we are able, we try to live in an environment that brings us close to natural things, where man does not dominate leaving the stamp of his designs and desires, where natural forces work unimpeded, where natural laws reveal themselves easily to the patient and quiet observer.

Suan Mokkh is the first forest Wat in modern Southern Thailand. Trees and vines are everywhere, not planted; beautiful, fresh, surprising. They were here first, then the Wat with its structures fit in and around. It is a privilege to live among trees, rocks, streams, mouse deer, langur, and gibbons, birds singing unseen and suddenly flashing color-movement, snakes harmless and deadly, and untold insects (three inch grasshopper plops onto typewriter and springs off). In the old days, tigers and leopards used to come down when hungry to eat a dog. The privilege becomes poignant as I read how the world's forests are dying of poison, pillage, and war, or remember the chain-saws shrieking just across the Wat's fence my first year here.

I'm typing at a hut in the back of the Wat, one of about forty spaced 20 to 30 meters apart. I type mainly at night by kerosene lantern. Remnants of the afternoon rain drip from the tree leaves, various cicadas chirp and hum in their chosen crescendos, termites migrate (do they mimic big city commuters or vice versa?), the fading moon rises. Looking up from the keyboard there is darkness, tree shapes, shadows, everyone's home. Regularly, I go down from this porch (the hut is raised four feet off the ground) to tend a fire and pour its water for tea or to pace barefoot on the red sandy soil laid bare around the hut, attending to my breath as a kind of walking meditation. Other times, when there is light, I walk around, stand, stoop, to observe vine shoots, ferns, mushrooms, mosses, chameleons, puddles, and the geopolitics of various ant races. Events, transformations, patterns, cycles gently manifest to the heart that seeks to be at peace with nature. In human society we live in the complex world of language, ideas, beliefs, culture. But this more simple, this ego-less world, is for us to live in, too. Here are constant resources for reflection and contemplation about life, its meaning and purpose, the ways of living, peace. Am I worthy of this seventy foot tree? Will I listen to its Dhamma? What do this pair of thrush teach through their nest building on the porch? Who is the ancient monitor lizard basking regally in the sun?

To live our lives in peace with other people we must learn to dwell in natural silence. For only through an understanding of silence can we survive in the complex language worlds of human relationships, not getting lost and remaining sane, whole, healthy, unselfish. With trees we can easily enter a much freer dialogue where everything is open, where there are no games to put on, and each expression of Dhamma — including us — can be what it must be and do at that moment. Trees teach us how to look at each other without fear, desire, envy, conflict.

The woods and these little huts are ideal places for meditation. In the Buddha's time, the Bhikkhus were wanderers who settled down only for the three months of the rainy season. Generally, they stayed in the countryside and woods, not too near villages and towns. Such wandering is more difficult now; “civilization” takes up all the space. So we gather into monastic communities. Still, always, we must look into our own hearts and learn there the Dhamma, the truth of our lives and duties. At Suan Mokkh we use a system of meditation taught and practiced by the Lord Buddha both before and after his enlightenment. It is called Mindfulness with Breathing (ānāpānasati)5 The breath too is natural. It is soothing and vital with many lessons for revealing the secrets of life. No need for words and theories. Just learn from life itself, within ourselves.

Any large monastery must have a certain number of communal buildings, especially any center that is dedicated, as Suan Mokkh is, to teaching large numbers of visitors, lay and religious. Such buildings have been built out of necessity, in as functional and economical way as possible. Although some are a bit eccentric, they fit in with the forest, each giving space to the other. But whenever possible, no structure was built and nature's gifts used instead. The best example of this is our “temple” (uposatha), a consecrated area necessary in any full-fledged Wat. In Bangkok, the temples are rich, ornate, glittery buildings. At Suan Mokkh it is a hill scattered with rocks, with trees for pillars and the sky for the ceiling. A layer of sand was only recently added, as was the lone Buddha image, made for our fiftieth anniversary. It is washed by rain, cooled by the wind, and decorated by ceaselessly falling leaves. Lizards come and go as they please.

Suan Mokkh's main lecture hall is the slope leading from the gate to the base of Golden Buddha Hill with the temple on its top. Rocks have been moved, collected, and stacked to create a terrace — rimmed by a long curved seat for the monks — that acts as a “stage.” As the auditorium spreads down the slope, boulders, benches, and bare sand provide seating space for thousands, although audiences usually range from a few dozen to a few hundred. The trees provide shade, background harmony, showers of leaves, towers for lights and electrical wires, and playgrounds for birds, monkeys, squirrels, and the cicadas that often compete with the sound system. Then, scattered throughout the Wat are clearings, circles of gathered boulders, nooks and crannies where we can chat, read, rest, meditate, and try to understand nature's law and our duty within it.

THE TEACHER AND DHAMMA

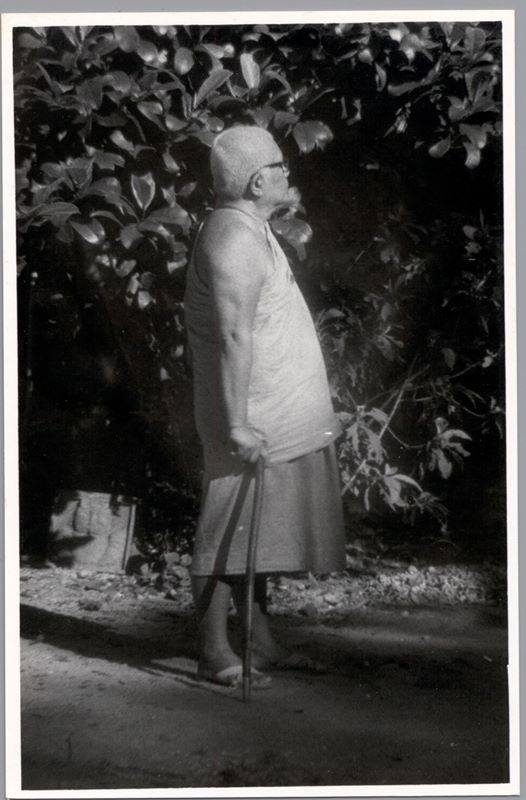

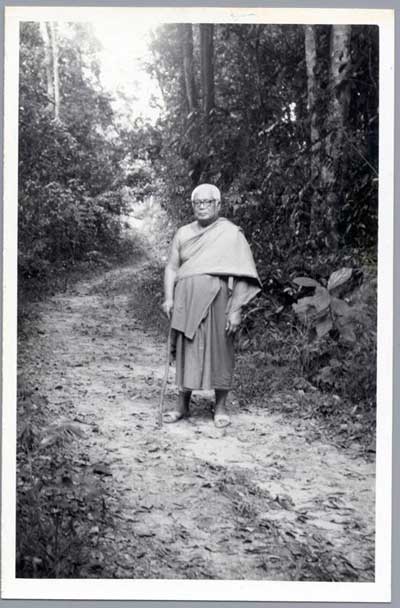

Visitors usually find Ajahn Buddhadāsa sitting on a bench in front of his residence. He is surrounded by plants, potted and wild, and by lotus ponds. Guests are invited to take another bench and, if willing, engage in a discussion of Dhamma. Chickens, cats, and dogs wander in and out, no more the owners of the place than anyone. Ajahn Buddhadasa is aware of the contrast with those Wats and religious residences where more emphasis is put on ceremony, material splendor, and physical comfort than on the simplicity, poverty, and message of the great teachers in all traditions. Sometimes he teases the experts from the government, United Nations, and so-called charity organizations who meet in fancy hotels and air-conditioned halls to discuss the problem of the poor. Only strong rains chase his discussions here under a roof, but not so far as to go indoors.

Visitors usually find Ajahn Buddhadāsa sitting on a bench in front of his residence. He is surrounded by plants, potted and wild, and by lotus ponds. Guests are invited to take another bench and, if willing, engage in a discussion of Dhamma. Chickens, cats, and dogs wander in and out, no more the owners of the place than anyone. Ajahn Buddhadasa is aware of the contrast with those Wats and religious residences where more emphasis is put on ceremony, material splendor, and physical comfort than on the simplicity, poverty, and message of the great teachers in all traditions. Sometimes he teases the experts from the government, United Nations, and so-called charity organizations who meet in fancy hotels and air-conditioned halls to discuss the problem of the poor. Only strong rains chase his discussions here under a roof, but not so far as to go indoors.

This appreciation for nature is one of Suan Mokkh's way of honoring all Buddhas (the Ones Who Know, the Awakened Ones). The man who came to be called “The Lord Buddha” was born outdoors, in a grove of trees, on the ground. All the major events of his life happened in similar circumstances: the Great Awakening under the Bodhi tree, the first sermon in the Deer Park at Isipatana, and the passing into Parinibbāna6 at his body's dissolution. Many hours of , untold miles walking through the Indian countryside, and forty-five years of tireless teaching mostly took place outdoor, beneath trees, on the earth (perhaps with a pile of leaves or grass covered by a simple cloth as a seat). Nor was the Buddha unique in this closeness with nature. Christ, Mohammed, Lao Tzu, and most of the “Ones Who Know” spent much of their time in the “desert” or “wilderness.” And what of their disciples living in this world of petroleum derivatives, steel, and silicon wafers? The Buddha's advice remains the same. Bhikkhus, these bases of trees, these quiet places, you ought to practice diligently. Don't be careless, don't live as a person who will have regrets later.7

WE MUST HELP OURSELVES

Buddhadāsa Bhikkhu had six Rains when he returned from Bangkok to found Suan Mokkh.8 By then he had passed and subsequently taught the recommended basic studies and had begun the formal Pāli studies necessary for status and advancement in the ecclesiastical hierarchy. Although he was dissatisfied by the worldly atmosphere and trappings of those studies, by their conservatism, and lack of free thought, he gained from them a solid enough understanding of the Buddha's teaching to go independent. The decadence, busyness, filth, and noise of Bangkok — even sixty years ago — sickened him, so he sought a proper place to put the teachings into practice. He moved into an abandoned Wat in the woods near the town of his birth and began his exploration in earnest. When younger bhikkhus and novices heard of Suan Mokkh and came to stay there, he required that they too have enough study knowledge, commitment, and maturity to be self-reliant. Basic training was available elsewhere; Suan Mokkh sought a deeper practice.

The Buddhist analysis of the human dilemma is that we bring suffering upon ourselves and others through our own ignorance. The naturally pure mind is deceived and lured by sensual experience. Things are taken to be permanent, satisfying, beautiful, ownable, and most profoundly, to be selves.9 Viewing our lives and world in such a way, we pervert the basic experiences of seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, touching, and knowing (including all the mental processes such as thinking, feeling, remembering); along with the feelings (pleasant, unpleasant, and neither-pleasant-nor-unpleasant) that arise toward those experiences; into craving, lust, hatred, delusion, worry, fear, and all forms of selfishness. Such deluded thinking and acting is misery, all of which is rooted in our own blindness and misunderstanding. Ultimately, then, the solution is to remove that ignorance. And if that ignorance is within our own hearts-minds, how could anyone else remove it for us? To depend on outside help is childish; we must cure ourselves.

This being the case, Buddhadāsa Bhikkhu set off to cure himself and never fell under the delusion that he could cure others. He simply wanted to study, practice, and penetrate to the heart of the Buddha's Dhamma, and never had intentions to set himself up as a teacher. Others who shared the goal were welcome to use this garden for their spiritual studies and experiments, but only as friends and equals. Although he ended up being the older brother, due to his knowledge and experience, he didn't dominate or tell others what to do. That might give them an excuse to shirk their own responsibility and become dependent. Even as the role of teacher came to be necessary, as Suan Mokkh grew and became well known, he always demanded that people think and investigate for themselves, rather than just memorize and believe in teachings. When and where he could, he has been ready and willing to be a guide and friend, but he has no illusions of doing more. The Buddha himself said,

“Striving is your own responsibility, the Tathāgatas (Awakened Ones) only point the way.”10

I emphasize this point because many monasteries, Buddhist and other, require strict obedience. While obedience helps to avoid selfishness and pride, and while obedience in worldly matters allows them to be taken care of simply and efficiently, there is no authority to obey in spiritual matters other than the Dhamma itself. One must hear and listen to Truth oneself, and obey it willingly. At Suan Mokkh, it is felt that one should start doing so immediately. If one must have it interpreted by another today, whenever will one learn to hear and live directly?

Rather than one person try to transform another, Dhamma-Nature-Law must be allowed to do the work, the shaping and transforming. Here, even the selfish and immature are given space to grow up into unselfishness. The more knowledgeable and experienced should be able to watch and encourage with kindness, compassion, and equanimity. If too much importance is placed on conforming to some external form, the heart will never conform to Dhamma. Once again, this is in line with the Buddha's example. Rather than call himself a teacher or divine messenger or god, he simply claimed to be a kalyāna-mittā (good, noble friend).

This is not to say that one can do nothing to help another. The Middle Way avoids the extreme of indifference, non-caring, and insensitivity as much as it shuns bossiness and domination. Both extremes are forms of irresponsibility, or responsibility primarily to selfish impulses. True responsibility lies in between, in Dhamma. The spiritual guide, then, is first of all someone who has walked the way of Dhamma sufficiently to point out that way to others. The knowledge and experience gained from direct spiritual living can be expressed and explained in various ways to help others to discover how they too may live this life. And the presence of a truly unselfish, even selfless being shows beginners that it can be done, provides a tangible example of the teachings for those who have not yet found it deeply in themselves. So far, Suan Mokkh as been blessed with a spiritual friend who gives powerful and challenging teaching along with an impeccable example.

Self-reliance is not thrust on people, since few of us have been prepared for it. Anyone coming for a long stay is expected to have completed basic studies first. Once here, he has many opportunities to experiment, study, and occupy developing minds in useful ways. Depending on individual abilities, proclivities, and needs, one could build one's program from activities such as daily chanting of scriptures, meditation, scriptural study, translation, teaching visitors and school children, helping with traditional ceremonies, community service, construction work, painting and sculpture, transcribing tapes, publishing, looking after guests, lectures and classes, discussions, physical labor, mechanical and electrical work. No one pattern is expected. Everyone is free to use their knowledge and skills to benefit the Wat and practice Dhamma. And one can change, adapt, and experiment as one needs. In support of this Ajahn Buddhadāsa gives frequent lectures and is available for advice to keep everyone straight on the fundamental principles of Dhamma that are applied through the various activities one undertakes, if one is sufficiently mindful and wise.

RECOVERING PRISTINE BUDDHISM

It does not take a very careful reading of the Buddha's discourses (or the words of Christ recorded in the Bible) to realize that religion nowadays is much different from when the Master lived. Some may say that the Religion doesn't begin until after the Great Teacher dies and that it's all down hill from there. Ajahn Buddhadāsa, however, feels that the original spirit can be rediscovered or recaptured. To do so it is helpful to recreate the original conditions where possible and elsewhere adapt our modern ways to recollect and reflect how the Great Teacher lived and taught. Thus, many aspects of Suan Mokkh try to recapture the spirit and feel of “Pristine Buddhism.”11 Important examples have been discussed above.

It does not take a very careful reading of the Buddha's discourses (or the words of Christ recorded in the Bible) to realize that religion nowadays is much different from when the Master lived. Some may say that the Religion doesn't begin until after the Great Teacher dies and that it's all down hill from there. Ajahn Buddhadāsa, however, feels that the original spirit can be rediscovered or recaptured. To do so it is helpful to recreate the original conditions where possible and elsewhere adapt our modern ways to recollect and reflect how the Great Teacher lived and taught. Thus, many aspects of Suan Mokkh try to recapture the spirit and feel of “Pristine Buddhism.”11 Important examples have been discussed above.

Amusingly, attempts to return to the way things were done in the early days are often viewed as unorthodox or heretical. People tend to take the status quo with which they are comfortable, rather than the original teachings, as their basis for comparison. They become so used to their own habits, beliefs, opinions, and traditions that they never stop to reflect, “Is my way the only way?” “Was it always like this?” “How did the Buddha do things?” Thus, many people were shocked that Suan Mokkh for many years had no public Buddha images and took the fact to be a sign of disrespect. The intention, however, was one of deep respect and understanding. Originally, Buddhists had the wisdom to realize that the real Buddha could never be portrayed in a physical medium or form. In the oldest Buddhist art, such as the stupas at Amaravati, Sanchi, and Barhut, there are no attempts to represent the Buddha as a human body. Instead, there are Bodhi trees, Dhamma Wheels, and empty spaces symbolizing the enlightenment, the Buddha's Dhammakāya (Truth-Body) and the voidness (suññatā, emptiness of self and soul, I and mine) realized and exemplified through perfect selflessness. It wasn't until Greek immigrants brought their modeling talents and religious materialism to India that the Buddha was turned into an image. While helpful for instilling faith in children, such images are the source of much confusion, which may never be outgrown. Thus, Suan Mokkh strives to instill a deeper understanding of Buddhahood from the start.

Suan Mokkh tries to heal the artificial and harmful fragmentation of Buddhist life into disjointed pieces and practices. Spiritual practice is life, an organic whole; to dissect it is to disfigure and even kill it. Yet monks have long distinguished between a study camp of scholars and urban monasteries, and a practical camp of meditators and forest dwellers (either as wanderers or in small forest monasteries). Such a distinction didn't exist in the Buddha's time, although different disciplines showed varying inclinations toward solitude and community life, learning and mental cultivation. Later, with institutionalization, growth of monasteries, and the formation of universities, it seems that bhikkhus chose one camp or the other, rather than integrating study and practice in a personally relevant way. The Commentarial tradition that became dominant centuries after the Buddha, and now exists under the name “Theravāda Buddhism,” has enshrined the distinction. A bhikkhu might take up the study approach in a city monastery for a while and then go off to meditate, or do the reverse, or never change. But mixing the two aspects of learning in the same person at the same time in the same place does not seem to have happened much, especially in Thailand.

When Buddhadāsa Bhikkhu took up earnest and solitary practice, he soon found that he lacked sufficient understanding to practice thoroughly, and so his studies continued. He realized that study and practice must guide, support, and correct each other. The Pāli scriptures are full of practical information on all aspects of meditation and spiritual living. The knowledgeable and reflective student can find in them all the advice he needs. Meanwhile, daily practice enables him to distinguish what is truly relevant to his needs from what is inappropriate, academic, and superstitious. What remains is a simple, straightforward, unified approach.

Suan Mokkh has reduced the number, extent, and elaborateness of traditional ceremonies. Rituals are not considered efficacious enough, in terms of spiritual development, to warrant much of the bhikkhus' energy and attention. They are not abandoned altogether, however, when they contain sufficient meaning, and in sensitivity to the feelings of those who depend on them. It is doubtful that the bhikkhus in the Buddha's time did anything more than simple observances on the Full and New Moon days.12

The Thai people, like all cultures in adopting a religion, have added on their own seasonal holidays, folk beliefs, and customs, some of which have nothing to do with the Buddha or his message, and others in which the original meaning has been forgotten. In the first case, Suan Mokkh refuses to participate. No crude superstitions are tolerated, although they're always trying to sneak in. In the latter case, the ceremonial aspects are simplified and the spiritual meaning and value stressed. Thai customs are of course followed, but in simple ways that can support Dhamma understanding rather than mere emotional gratification. Not only is this approach courageous and daring (in any time or culture13), it takes much hard work. It is no easy matter to explain the deeper significance of holidays and traditions to “believers” more intent on warm feelings and fun. These explanations must be repeated year after year, not only for the local villagers, but for school teachers, soldiers, governors, academics, monks, and foreign scholars.

These are merely some superficial examples of Suan Mokkh's attempt to recover Pristine Buddhism. The most important aspect of the attempt involves taking a “new look” at the basic and essential teachings, especially those overlooked by traditionalists. This has stirred up the most controversy.

DUTY: WORK AND SERVICE

Every monastery depends on physical work, ranging from preparation of food to maintenance. Sometimes, the lay supporters supply and arrange for everything, leaving the monks to perform ceremonies, study, teach, meditate, and other such “holy” acts. More often, especially in rural areas, the monks must do much of the work themselves, becoming skilled, especially in construction work. Unfortunately, this work is seldom seen as Dhamma practice — necessary, yes; spiritually valuable, no. This misunderstanding can create frustration and confusion in the bhikkhus who must do such work and yet see it as separate from their spiritual practice and growth.

At Suan Mokkh, any necessary work is considered a duty, and duty is one meaning of Dhamma. Doing duties is practicing Dhamma. Cleaning toilets, as much as scriptural study and meditation, is necessary, therefore important and valid practice. In fact, one is less likely to feel pride over a toilet properly scrubbed than, say giving sermons. Yet, there is a satisfaction in it that brings joy and serenity, which can in turn lead to deepening wisdom.

In the early days, when only one or a few bhikkhus lived at Suan Mokkh, the work was small and could be handled easily by Ajahn Buddhadāsa and anyone staying with him at the time. Later, as Suan Mokkh grew, there was a need for larger projects and coordinated work. Thus began a tradition know as Labor Day. Each month there are four lunar observance days. The day before each of these observances is an opportunity for the monks and novices to get some exercise and clean themselves with sweat. Our hearts are defiled by selfishness, so we clean them by unselfish work. Doing so once every seven or eight days doesn't take away from other duties and accomplishes tasks on which the Wat depends.

As Suan Mokkh grew and Ajahn Buddhadāsa's reputation spread, it became necessary for certain work to be done regularly, often daily. In an informal and voluntary way, different bhikkhus, and sometimes lay residents, take responsibility for receiving and aiding visitors, teaching individuals and groups, recording lectures and copying tapes, transcribing talks, translating, maintenance, and looking after new monks. There are no positions or offices, and no administrative structure. Each does work that suits his skills, interests, and needs, which he considers valuable and satisfying. A small group of nuns and lay women also help out, especially in the kitchen.

One last bit of work is common to all forest Wats — sweeping the leaves, twigs, and branches that continually fall from our trees. Each hut has a strong broom (made from the ribs of palm fronds) and others are scattered liberally throughout the Wat. Everyone helps to keep living areas, public areas, and pathways clear. The never-ending task teaches patience and working for its own sake. This work is never finished, a leaf always falls upon the ground one has just swept. That's how it goes — impermanence, thusness. The value is in the working, in serving unselfishly: “Dhamma sweeps the heart while the broom sweeps the ground.” External cleanliness helps cultivate a clean, undefiled mind. And when it is done without any grasping and clinging, when there is only sweeping and no sweeper, then “void-mind” is uncovered and there is direct living in Dhamma.

TEACHING

As has been implied already, Suan Mokkh has always seen teaching as one of its duties, in fact, a central duty second only to spiritual study, practice, and realization. Anyone who has benefited from the teaching in some way has a duty, in turn, to keep those teachings alive, to pass them along to others, to maintain the religion. Even before founding Suan Mokkh, Buddhadāsa Bhikkhu delivered frequent sermons at other Wats in the area. Later, he was kept quite busy speaking around the province, throughout the southern region, then more and more in Bangkok, and finally in the central and northern regions. Other monks from Suan Mokkh have been recognized as knowledgeable, inspiring, and creative speakers. Now that Ajahn Buddhadāsa never travels, many of his monks, former students, and others influenced by him — including many lay people — are helping to keep alive and deepen understanding of the Buddha's Dhamma in Wats, schools, hospitals, government offices, non-government organizations, social activist circles, and Buddhist groups (often formed by the employees of medium and large sized companies). Suan Mokkh is by no means the only source of teaching energy, but the number of respected teachers — especially lay — coming from somewhere outside of Bangkok and outside the traditional mainstream is extraordinary. Many disagree with ideas coming from Suan Mokkh, but no one in Thailand can be indifferent to them. Over the years, controversy and criticism has lessened but not disappeared; this is taken to be a good sign.14

As has been implied already, Suan Mokkh has always seen teaching as one of its duties, in fact, a central duty second only to spiritual study, practice, and realization. Anyone who has benefited from the teaching in some way has a duty, in turn, to keep those teachings alive, to pass them along to others, to maintain the religion. Even before founding Suan Mokkh, Buddhadāsa Bhikkhu delivered frequent sermons at other Wats in the area. Later, he was kept quite busy speaking around the province, throughout the southern region, then more and more in Bangkok, and finally in the central and northern regions. Other monks from Suan Mokkh have been recognized as knowledgeable, inspiring, and creative speakers. Now that Ajahn Buddhadāsa never travels, many of his monks, former students, and others influenced by him — including many lay people — are helping to keep alive and deepen understanding of the Buddha's Dhamma in Wats, schools, hospitals, government offices, non-government organizations, social activist circles, and Buddhist groups (often formed by the employees of medium and large sized companies). Suan Mokkh is by no means the only source of teaching energy, but the number of respected teachers — especially lay — coming from somewhere outside of Bangkok and outside the traditional mainstream is extraordinary. Many disagree with ideas coming from Suan Mokkh, but no one in Thailand can be indifferent to them. Over the years, controversy and criticism has lessened but not disappeared; this is taken to be a good sign.14

In the past, travel to Suan Mokkh was difficult, and most of its teaching work was done by bhikkhus traveling to the audience. Since the building of the Asia Highway at our gate, and with rapid increases in bus transportation and personal car ownership (in addition to the rail service available since the beginning), the number of visitors has grown from year to year. Almost every bus tour group traveling south stops at least to stretch their legs. We hope that they can catch some peace of mind among the trees before continuing their hectic schedule, and when time permits, we invite them into the Spiritual Theater for some Dhamma nourishment. The Theater is a large hall covered on the outside with copies, made here, of ancient relief sculpture from the earliest Buddhist shrines in India and inside with an eclectic collections of paintings, original and copied, from all Buddhist schools, other religions, folklore, fables, and flower catalogues. There are always bhikkhus available to help visitors discover Dhamma meaning in these paintings. For most the Theater is strange but interesting, something that might spark some spiritual inquiry. While sight-seeing at Wats is common, taking the time to examine one's own heart is not.

Housing is available for those who wish to stay longer. As in most forest Wats, there is no charge and no time limit. Study programs are arranged for the many groups that come for a few days to over a week. There are groups of high school and university students, teachers and civil servants, monks and novices, development workers and ordinary villagers, and even foreigners. Some weekends and during the school holidays the older bhikkhus are not given much time to rest. Most of the programs include an introduction to meditation and daily sittings. Further, meditation courses are organized regularly for foreign travelers, some who come out of curiosity and other who come to Thailand specifically to study Buddhism. The instruction is in English, with Western and Thai monks helping out. In turn, Thai groups have asked for similar courses in Thai, which now are happening as well.

Another recent development of special interest is that Bangkok's oldest and most famous hotel, under the leadership of the personnel director, who is a practicing Buddhist, is bringing down groups of its own staff on a regular basis. The hotel has found that higher pay does not make for satisfied and happy staff. In fact, more money leads to more drinking, debt, and other personal and family problems. The response, which is popular among staff and showing positive results, is to help them find meaning in their lives through an understanding of Buddhism that goes deeper than beliefs, superstitions, and traditional ceremonies. The message is simple: Selfishness never brings true happiness; genuine unselfishness is immediately happy. Most of the staff has come, and many are asking for a second visit.

Because Suan Mokkh is not like other Wats, many visitors are given a fresh look at Buddhism, especially those who have lost interest in the traditional, and often outdated, Wats. Suan Mokkh is more like a park; it lacks the imposing and expensive buildings that intimidate as much as they awe. The atmosphere is both informal and committed, lively and relaxed, challenging and friendly. This can be disarming, helping people to drop their defenses and open their hearts, and often kindles a bit of childlike innocence. While many merely take the opportunity to unwind and relax before rushing back to increasingly chaotic modern life (which Suan Mokkh doesn't begrudge them), some are touched profoundly. The work and service is its own reward, but the peace and joy in the eyes and smiles of others is a pleasant bonus. Suan Mokkh doesn't claim credit for these changes in people. They have done the work themselves and must continue to do so. And much of the teaching is done not by words and painting but by nature. Who can really know the transformation and awakening in others' hearts? It's enough to begin to see it in oneself and cultivate it as far toward selflessness as one can. Serving others serves the Dhamma, and when there is no “self” to be served there is true peace.

MONKS: NO ONE SPECIAL

No matter how unique, innovative, or controversial, everything and everyone without exception meets in Dhamma, in nature, in ordinariness. In trying to share our understanding of Dhamma with others, bhikkhus should not hold themselves up as an ideal to follow; I for one am far from ideal. We are monks, they are not, but our common humanity runs deeper than any distinction. There is only one truth, one Law; the Buddha's teaching speaks to all human beings. Naturally, the circumstances of our lives must vary and so too our approaches to Dhamma. We each must realize our own duty, no one is “holier” than another. Too often, the “full-time religious” (do any truly live their religion full-time to the depths of the heart?) are put on a pedestal to be respected, even worshipped, leaving the worshipper feeling lower and lesser and confused. Humility is proper, but denigration one's own spiritual potential kills. As much as Thai custom allows, Suan Mokkh tries to avoid putting the monks above others. The need is for everyone to bow to the Dhamma in their own hearts. Bowing to anything else is superstition.

To avoid becoming special, to perform its duty successfully, the Wat must be relevant. Thai Wats used to be the center of village life and traditional Thai culture. With rapid modernization, capitalization, and urbanization, the Wats tend to be more and more on the fringe, except when they are co-opted. They are kept separate for special days and activities, rather than being a vital part of daily life. Sometimes a Wat tries to get up-to-date with gadgets, marketing, and slang. Usually it gets swept along and loses its spiritual grounding. Or it just holds tight to its traditions and watches the congregation get old, then burns them one by one.

When the Wat, church, or synagogue can no longer speak its rightful message in terms coherent to its community, then society becomes dead within its heart. The challenge in these increasingly confusing, materialistic, and selfish times is to keep the spirit alive and to rejuvenate the traditions, to maintain the spiritual ground and to speak with the community in spiritually practical words. Suan Mokkh is determined to keep pace with the rapid changes in society, not merely to be modern, not to follow, but to lead. No one thinks it is easy to do so. We must be dedicated, sensitive, open, inspired, creative, and on-the-ball. No matter, we prefer this most difficult service work — teaching Dhamma and all the inner work it entails — to watching our friends rot in a spiritually meaningless world.

RESOLUTIONS

For many years Suan Mokkh has operated in line with “Three Resolutions.” These are to try our best

• To help everyone penetrate to the heart of their own religion;

• To create mutual good understanding among all religions;

• To work together to drag the world out from materialism.

Muslims and Christians, the main religious minorities in Siam, all religious people, and even those who shun religion have always been welcome here. Out of curiosity, goodwill, and necessity, Suan Mokkh wishes to meet with all religions. The basic principle is to establish mutual good understanding. This means that each party expresses its spiritual understanding as clearly as it can, with all other parties listening open-mindedly. There is friendly give and take. Agreement is not expected but is found where possible. Differences are noted, but the emphasis is on what we have in common and what each can contribute to the battle against selfishness. There is no wish to form some One World Religion. People have different cultures, backgrounds, education levels, and mental abilities. Therefore, a variety of religions is necessary. The key is to prevent that variety from being a source of competition, argument, and conflict.

Suan Mokkh's emphasis on nature helps the dialogue. Everyone can appreciate this most common denominator. No religion claims nature for its own; we can all respect, share, and learn from it together. Self-reliance and responsibility, no side setting itself up as teacher, openness and freedom of thought, dedication to hard work and service to humanity, simplicity, and directness: All these are qualities that will help each of us to get to the deepest spiritual core of our traditions. Then we can met without fears and schemes in true sisterhood and brotherhood. And for those who dare, the fresh look Suan Mokkh takes at Buddhism can explore all traditions.

Suan Mokkh's latest project is the development of an International Dharma hermitage. One of its uses will be for holding meditation courses and group trainings. Ajahn Buddhadāsa is most interested, however in using it to bring together spiritual people from all of Thailand's religions to further mutual good understanding and cooperation against rampant materialism and moral decay. If such meeting are successful, and they will not be so difficult to arrange, he would hope to do the same on an international scale. For now, Suan Mokkh is waiting to see who is interested.

• • • • •

ENDNOTES

1 Originally appeared in Monastic Studies (No. 18, Christmas 1988), The Benedictine Priory of Montreal, Montreal, Quebec. First electronic edition with kind permission.

2 Bhikkhu (Pali) means "beggar" and was one generic term for mendicants in India at the Buddha's time. It also means "one who sees the fearsomeness and danger" of ordinary worldly existence with its constant ego-birth and -death. It is often translated by "monk," although originally more like the wandering friar than the settled cloistered monk. The female counterpart, called "bhikkhuni," no longer exists in Southeast Asia; however, a movement to re-establish the lineage has been developing.

3 Buddhadasa means "Servant of the Buddha." He took this name just before starting Suan Mokkh and prefers it over later titles and honors. Out of respect we usually call him "Ajahn Buddhadasa"; ajahn (Thai) means "teacher, master." His brother, who took the name Dhammadasa, still leads the Dhammadana Foundation, which supports Suan Mokkh and handles its business affairs. For more information on Ajahn Buddhadasa's life and work see The Life and Work of Buddhadasa Bhikkhu, a video documentary produced by the Foundation for Children, Bangkok, 1987; and a growing number of translations by this writer and others.

4 Dhamma is Pali spelling. Dharma is Sanskrit. It is variously defined and used in different traditions, schools, and sects.

5 For details see Buddhadasa Bhikkhu, Mindfulness With Breathing: Unveiling the Secrets of Life, Bangkok, 1988. New edition published in the USA by Wisdom Publications, Boston, 1996.

6 This word is difficult to translate for nothing can be said about an enlightened being when the body dies. "Perfect, thorough coolness" suits Suan Mokkh's understanding of the word.

7 Samyutta-nikaya, IV, 145 and numerous other places in the Discourses.

8 The seniority of bhikkhus is measured in the number of three month long "Rainy Season Residences" (vassa) they have passed. Traditionally, after five rains a bhikkhu is considered experienced enough to live on his own away from teacher.

9 Pali, atta; Sanskrit, atman; Latin, ego; self, soul: The Buddha taught that "sabbe dhamma anatta," all things are not-self. He made no distinction between true self and false self, or between self and eternal soul. Life, experiences, phenomena exist, but nowhere is there to be found anything that can rightfully be called "self," there is no eternal substance or abiding, independent essence which can be taken as "I," "mine," or "myself."

10 Dhammapada 276.

11 By "Pristine Buddhism" we mean the teaching and practice before the disintegration into differing sects and schools, with their polemics and dogmatics.

12 The uposatha, an ancient Indian practice, was adapted by the Buddha into a meeting for exhortation regarding the teaching and training (patimokkha), then later, for recitation of the growing training discipline (vinaya-patimokkha).

13 Imagine taking monstrous sporting events and their TV coverage away from Americans.

14 If everyone agrees with what we say, either they don't understand what we're saying or what we are saying is meaningless mush.