Buddhadasa on Economics: An Interview with Buddhadasa Bhikkhu

By LEONARDO CHAPELA - September 8, 2017

This interview, conducted by Dr. Leonardo Chapela and translated from the Thai by Santikaro Bhikkhu in 1991 at Suan Mokkh, was first published in A Single Bowl of Sauce: Teachings beyond Good and Evil, Bangkok, Buddhadāsa Indapañño Archives, 2017, pp 115-139.

NOTE: The translator participated in the discussion quite a bit, sometimes amplifying on Buddhadāsa Bhikkhu’s statements, sometimes adding his own observations. These have been allowed to stand for they were an integral part of the discussion and for the most part repeated ideas Ajahn Buddhadāsa has expressed elsewhere (in his writings, talks, and personal comments). Longer comments by the translator are attributed directly; shorter comments are in {brackets}.

DAY ONE

Leonardo Chapela [introducing himself]: Thank you for your time and the opportunity to interview you. I would like to include this interview with an article I wrote, “The Defilements of Western Culture.” It is an essay towards a political economy of Buddhism.

Ajahn Buddhadāsa: And don’t the defilements (kilesa) of the West (farang) come down to just selfishness?[1] No matter what defilement, of whoever, wherever, we must accept that they all come from selfishness – every defilement.

LC: Various social scientists in the West claim that religion has an influence on morality which, in turn, influences economic behavior. Sometimes the influence is great and other times small. For example, in Europe, after the Protestant Reformation, Protestant beliefs joined certain economic ideas and promoted modern capitalism. The question is: What influence has Buddhism had on human behavior and economics? Have you seen any interesting indications that Buddhism has influenced human social and economic behavior?[2]

AjB: The problem is that the majority of human beings in this world, even in the so-called Buddhist countries, have not actually received Buddhism and so it is difficult to say much to your question. The current issue is how to make Buddhism available to people, so that is what we’re thinking about. When we speak about Buddhist economics, the problem is how to help people to get the most valuable thing in life. This is our job now, which is a spiritual economics rather than a material economics.

LC: Is the thing which has the highest value Nibbāna?

AjB: There should be two objectives in Buddhist economics, one worldly and one spiritual. The spiritual objective or final goal is Nibbāna.[3] When speaking of material economics, the objective is right here, namely, peace in this world, a kind of peace which we can use in a worldly way. The highest good in this world and the highest good which is above the world must be distinguished in this way. Material economics and spiritual economics have different objectives.

Part of the difficulty is our vocabulary. I’m not even certain what the word “economics” means, but seṭṭhakica (economy as activity), seṭṭhasastra (economics as “science”), and seṭṭha mean “utmost excellence.” The Thai words (from Pāli and Sanskrit)[4] mean “utmost excellence,” but I don’t know what the English term “economics” means.

Santikaro Bhikkhu: Seṭṭha is a Pāli word which means “most excellent.” Here, of course, many modern Thais use the word seṭṭha-kica for economics, mainly in the modern Western sense, because this term was coined by Thai academics who had gone to study in the West and then returned with Western ideas. If you go back to the Pāli, the meaning of seṭṭha is “excellence.” In modern Thai, a millionaire is called seṭṭhī, but the Pāli term refers to inner or spiritual excellence more than material wealth. The latter is, at most, a reflection of the inner excellence.

What are the linguistic roots of “economics”?

LC: It’s a Greek word: oikos and nomos. Oikos means “house” and nomos means “administration.” So economics means “the administration of the house.”

AjB: To say that economics is the “administration of the home,” or even “administration of the world (loka),” is not adequate. Economics should be extended to lokuttara (above and beyond the world, supramundane), that is, the “administration of the transcendent.” There are two distinct levels: {the administration of the mundane (worldly) home and the administration of the supramundane (spiritual) home.}

The tools we use for success in spiritual economics can be applied to material economics. The highest tools can also be used on an ordinary level. Amusingly, it’s the same principle for both: for the highest spiritual economics we must use the utmost scale of unselfishness, that is, transcendence of self, while ordinary unselfishness is for success in worldly economics.

SK: As long as our economic system is based on selfishness, encourages selfishness, supports and protects selfishness, justifies and legitimizes selfishness, it will fail. Buddhist economics, therefore, must overcome selfishness in both the worldly and spiritual spheres.

LC: Does self-interest mean the same as selfishness or is there a difference? Is there a “safe selfishness” and a “dangerous selfishness”?

AjB: Selfishness involves kilesa – defiled, low thinking. But we don’t call “seeing in terms of oneself” through good thoughts “selfishness.” We must call it by another name. {Perhaps “self-interest.”}

Think of “self-development” and “self-respect.” In both of these, one cares and thinks about oneself, but they aren’t kilesa, they aren’t evil, low, or wrong. So we can’t call them selfishness.

SK: This distinction is important for understanding how proper spiritual practice is not selfish, but is caring about oneself in the right way, in a way that doesn’t harm anyone. To satisfy genuine needs – whether physical or spiritual – in the right way is not selfish. Of course, incorrect practice can be very selfish.

AjB: There are two kinds of caring about oneself: with kilesa and with wisdom (satipaññā). If it’s with wisdom, don’t call it selfish. Use another word. Buddhism teaches self-respect, self-development, self-responsibility, and self-reliance. None of them are selfish. They may be beneficial for oneself, but they are correct. So they aren’t called selfishness. If we speak more comprehensively, have the kind of self which isn’t selfish.

LC: Do we have any problems with the economic system known as capitalism? For the most part, capitalism stresses personal property.

AjB: That is totally selfish, it’s just for the individual, for the self. If capitalism is like that, it’s totally selfish. To be “selfish” for the sake of others isn’t selfishness, it’s for correctness. One is for our own benefit, the other is for the benefit of others or of everyone, {including oneself}.

SK: Is there a way to harmonize capitalism and unselfishness? Capitalism stresses that humans have the rights to possess property, wealth, commodities, the means of acquiring them, entertainment, etc. If individuals don’t protect these rights, the powerful will accumulate wealth to the detriment of others.

AjB: This is a new subject. But if we think in terms of having happiness, health, and comfort, can’t they be for others, too?

SK: The stress that capitalism places on personal property is selfish, because property is used solely for the benefit of the self – “my property.” Buddhism emphasizes the use of things for the sake of correctness, something that benefits everyone; this value is entirely different from selfish benefits. Often, when we talk about private property in the West, we have the idea that people should have the basic physical means to earn a living, to protect themselves, and so on. This attitude is considered a right to be protected so that powerful segments of society do not accumulate too much and oppress others. That is a different matter, but can we ask how all of these tools, even personal possessions, health, and happiness would be used for the benefit of others? Do we always have to stress that they are for one’s personal benefit?

AjB: There are two [Thai] words which we have spoken of often: seṭṭhī jaiboon (good-hearted philanthropist) and naitoon kradatsap (blotting paper capitalist). They will help us understand easily, seṭṭhī is a wealthy person, but her wealth is for the benefit of others. {Her business is actually to provide employment and livelihood for others. She shares her wealth and benefits society.} The other’s wealth, that of the naitoon kradatsap, is for himself alone. The blotting-paper capitalist sucks up everything he can touch, so that nothing is left. {One is a Buddhist ideal and the other is completely immoral.} In the West, do you have a term like “blotting-paper capitalist”?

SK: We have the term “blood-sucking capitalist.”

LC: Is the first one compatible with Buddhism? Is that kind of capitalism acceptable?

SK: Yes. Although we need not call them capitalists, having wealth, even having a great deal of wealth, is not incompatible with Buddhism. Whether one has a lot or a little wealth, the fundamental issue is how that wealth is used. Is it used for the benefit of others, for society? Or is it used solely for one’s personal benefit?

AjB: Perhaps you don’t yet have this term “good-hearted millionaire” in English, a person who is wealthy for the sake of others. If someone is wealthy for his own sake, he’s a capitalist or investor, not a seṭṭhī.

SK: In English, we have the word “philanthropist.”

AjB: Correct. That could be the same as seṭṭhī jaiboon.

SK: Sometimes, however, this philanthropy is merely a kind of show, where somebody who has accumulated wealth through immoral means then gives some of it away to get tax write-offs or ease his conscience.

AjB: That isn’t what we are talking about here, but it’s possible that somebody who obtained his wealth through immoral means could have a change of heart and then use his wealth for others.

SK: King Asoka is the traditional example of that. After violently expanding his kingdom, he had a change of heart and thereafter tried to run his kingdom morally. So we must carefully distinguish between wealth (or power) for the benefit of others and wealth for one’s own benefit.

AjB: Selfishness leads to being wealthy for “my sake” and unselfishness leads to being wealthy for “the sake of others.”

SK: Therefore, in Buddhism, whether one has much wealth or little, has much property or little, is not the issue. The issue is how the wealth and property is used. Correct?

AjB: A big seṭṭhī has many almshouses, a small seṭṭhī has only one almshouse.

[A short part of the conversation was not recorded when the tape was changed.]

The capitalist will treat his employees like employees or even like slaves, but the good-hearted wealthy person, the seṭṭhī, treats the workers as his children, grandchildren, or relatives. Therefore, there is a significant difference between the owners and managers who treat their workers and employees as being workers and those who treat the workers as their own children or relatives.

You should find clear simple terms in English comparable to seṭṭhī jaiboon and naitoon kradatsap.

SK: How about philanthropist and blood-sucking capitalist?

AjB: I’ve heard of “philanthropist,” but I don’t know what it means.

SK: Philos means “love” and anthropos means “people,” thus “one who loves people.” Nowadays, philanthropist is only used for rich people who give to charities and start foundations.

Tan Ajahn, what must we do to bring about the kind of economics which you describe? How can we get both ordinary people and the leaders to have this kind of economics?

AjB: This has to do with religion, it depends on the kind of religion that they follow, whether it’s a religion with self or a religion without self. What’s unique about Buddhism is the teaching that there is no true, abiding self;[5] not-self (anattā) is the basis of Buddhism. So there’s nothing to be selfish about. Religions like Hinduism teach that there is a self or eternal soul. Then they must deal with that self, must control it, so that it doesn’t become selfish. When one doesn’t feel that one has a “self,” one loves others automatically. So it isn’t necessary to teach about love. There is automatic love.

Nowadays, people aren’t concerned with correctness or about others, they only care about themselves. They’re all selfish. To study Buddhism, we must study the story of “not-self” (anattā), the fact that everything is not-self: the self which is not-self.

SK: Then to establish the kind of economics we’re talking about, or socialism, we must...

AjB: Must bring in unselfishness. Where it will come from is another question. We must set up unselfishness. So we must ask – from where will we get it? The way to do it is through education, the kind of education which is unselfish. We must teach our children so that they aren’t selfish from the time they’re little. Then they’ll grow unselfishly. {This education includes the family, culture, and religion, not just the schools.}

If we look around the world, we’ll see all kinds of crises. And every kind of crisis comes from selfishness. There’s no exception, all the problems come from our selfishness. Drug addiction, AIDS, pollution, destruction of nature, highway accidents, and crime all come from the same source: selfishness. All the low, evil, and undesirable things come from selfishness. If we teach this a lot, it ought to help.

Education must teach this matter as a central principle, repeatedly and at every level, from nursery school through primary and secondary, and including university and graduate. With all levels teaching unselfishness and destroying selfishness on higher and higher levels, the world will have peace.

LC: This is what should be taught, but it’s not happening. The different religions teach people to be good and to love their neighbors, but they don’t really practice what they preach.

AjB: We must accept that modern education in this world is wrong. The more clever they are and the more they learn, the more selfish they are. The more educated, the more selfish.

SK: Has there ever really been a kind of education in this world which doesn’t make for selfishness?

AjB: We must say that when education was still correct, when education was still in the hands of religion, {it didn’t make for selfishness}. But now education has been taken away from religion, it is in the hands of worldly people.

SK: Has it ever happened in reality?

AjB: I believe so. I’ve heard that originally Oxford and Cambridge were private schools attached to monasteries. The monks set up the monastic schools. They started as small schools and later grew into famous universities. Is this true?

SK: It is partly true, but the problem was that the monasteries weren’t very pure, weren’t that interested in religion.

AjB: Oh. But if it was a matter of religion, there was less selfishness.

SK: If one studies the history of Christianity in Europe during the medieval ages, you’ll find a lot of corruption. Monks and priests weren’t that interested in religion. They messed around in politics. The most powerful cared mostly about money and power, even some Popes were like that. And they had a lot of blood on their hands, because of worldly goals, not religious. Religion was merely a tool for worldly ends.

AjB: But if any religion has survived, there must be a part which is correct.

SK: Maybe five percent. The Vatican was filthy.

AjB: The Vatican doesn’t have much to do with it. This concerns religion. We’re talking about “gentlemen,”[6] those who are unselfish. Now all the gentlemen are selfish, the more a gentleman the more selfish. Now it’s the “selfish gentlemen.”

SK: Tan Ajahn has heard that Western universities originally had the purpose of educating gentlemen.

AjB: I’d like to ask an easy question: Whether in England, or wherever, are the gentlemen of three or four hundred years ago and the gentlemen of today the same?

SK: In Pāli, there is the word sappurisa. Its original meaning seems to be the same as the old meaning of “gentleman,” a truly noble person.

AjB: Sappurisa is a good gentleman.

SK: The Buddha then even used sappurisa as a synonym for the arahant, the perfected human being.[7]

AjB: So it has become the {false} gentleman who is selfish and the {genuine} gentleman who is unselfish.

LC: Regarding education, what is the role of meditation?

AjB: Meditation is for studying to see that there is no self, that everything is anattā (not-self): impermanence (aniccaṃ), unsatisfactoriness (dukkhaṃ), selflessness, voidness (suññatā), thusness (tathatā), and so on.

LC: From the perspective of Buddhism, should the people practice meditation?

AjB: It’s a tradition. Now we’ve thrown out the traditions, but in the past it was a tradition that to be a Buddhist one must meditate. They used to like daily meditation. It was a tradition going back a few hundred years ago, it still existed when I was young, but now it’s been abandoned.

SK: What kind of meditation? Ānāpānasati?[8]

AjB: That depends. Ānāpānasati was widespread and well-known.

SK: Do you have any evidence?

AjB: Evidence? This is what I was told. When I was a child, there were still some old people who said how things had been. In the wats (temples), that is, in the genuine ones but not necessarily every one, there was a place for meditation. In back, a grove of trees was set aside for meditation, for ānāpāna. There were good ones, bad ones, even crazy ones.

My uncle once explained to me about the way he meditated. He did ānāpāna. We can’t accept his way now because there was too much ritual involved and not enough Dhamma. {Nonetheless, meditation was common once, then abandoned later.} They called it ānāpāna.

Young men practiced it in order to fly. They wanted to be able to fly. They learned with selfishness, so what will they get? What’s the purpose of training selfishly? It’s no good.

LC: I’d like to ask about right livelihood. Some Buddhists scholars in Sri Lanka suggest right livelihood (sammā-ājīva) as the doctrinal basis for Buddhist economics. Do you agree? What is the relationship between right livelihood as a doctrinal teaching and Buddhist economics?

AjB: That’s too literal. The scholars are too attached to their books. Although theoretically correct, it won’t work if people are selfish. You can’t call it sammā-ājīva if there is selfishness. Full of selfishness, it becomes micchā-ājīva (wrong livelihood). This doctrinal point isn’t the real source of right livelihood.

You must find the doctrinal basis in sammā-diṭṭhi (right understanding). Don’t just look at right livelihood by itself. The starting point is right understanding.[9]

SK: Otherwise, you just get righteous groups saying “we’re pure” or “our livelihood is better than yours,” which is full of attachment. That never leads to peace.

LC: [A question about “Buddhist businesses in ordinary life” that didn’t record clearly.]

SK: Don’t let this concept become narrow or materialistic. A business isn’t Buddhist because of external or physical factors, but because of its spirit. It is natural that people engage in business. What makes it “Buddhist” is the unselfish spirit, and ultimately the overcoming of self, that is, “selfless business.” starting with the right understanding of unselfishness and developing the ultimate right understanding of selflessness or not-self, right livelihood will follow naturally.[10]

LC: And right understanding requires meditation?

SK: Meditation helps develop right understanding.

AjB: Now, education helps teach selfishness. All the new kinds of education cause more selfishness. The smarter people are, the more selfish.

SK: I think it’s time to end today. Another group has come.

AjB: Are you coming again? If you would like to discuss this more, you can come back tomorrow.

If we use the word “capitalist,” there’s a way to make it non-selfish, that is, to be good capitalists who do not carry blotting paper or sponges.

DAY TWO

LC: We have been talking about Buddhist economics. Some people speak of Buddhist economics as being the “Middle Way.” One thing I would like to know from Tan Ajahn is whether Buddhist economics calls for a middle way between Western style development and a spiritual path. It has been difficult to integrate Western style development and economics with spiritual values. So Buddhist economics is trying to find a middle way. How can we work it out? Can the Buddhist “Middle Way” integrate the two?

SK: I’m not sure how to translate that question. When the Buddha spoke of “Middle Way,” he didn’t mean a compromise between two things, such as you imply. Rather, he meant the middle path that avoids all extremes, such as indulgence in pleasure and indulgence in pain. Is your question, “What is the Middle Way of development?”

LC: What is his point of view about this? This question is by a Buddhist scholar from Sri Lanka who thinks this question reflects the position of most Buddhist scholars.

SK: Tan Ajahn, how can the principle of the Middle Way be applied to national development?

AjB: If we translate the word sammā, sammā, sammā correctly you have the Middle Way. When all eight are correct, you can develop everything. Right Understanding, Right Aspiration, Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Concentration: these eight kinds of correctness can develop everything. The Middle Way, as a principle in Buddhism, implies eight kinds of sammā (rightness or correctness). {In Buddhism, both practicing the Middle Way and development mean developing these eight aspects of correctness or rightness.}

SK: But isn’t that just for individuals? How does it relate to the collective? How can it be a principle for developing the country?

AjB: If correct, it works, when the individual is correct, his work is correct, then material things are correct, and so the body and mind are also correct.

The word sammā has two essential meanings. The first is correctness or rightness. The second is moderation or “the mean”:[11] sufficiency or non-extremism (neither too much nor too little), adequacy (enough to get the job done without being excessive).

SK: The difficulty with the way you phrased the question, just now, is that speaking of an intermediate “middle way” between, for instance, Western economic values and spiritual values, is not the Middle Way as understood in Buddhism.[12] Such a definition is more in line with Western thinking than with Buddhism.

AjB: There is no contradiction between the Buddhist way and the material, economic, and industrial kinds of development if these later areas are approached correctly. When the heart is correct, material things are correct and the body is correct, {resulting in sufficiency rather than the present extremism.} When our actions are correct, the results of our work and actions are also correct. Thus, everything is correct.

SK: There is no reason why this should limit development, if the development is correct.

The Middle Way is not just a compromise, as many people try to interpret it. Thoughts such as “the Western values are these, Buddhist values are these, the Middle Way is some way between them” are not representative of the Middle Way. The Middle Way is to avoid dualistic extremes.

AjB: Neither too individualistic nor too socialist, but to be correct both for the individual and the collective: {this is another meaning of the “Middle Way”}.

LC: One of the main assumptions in Western economic theory is that resources are limited and that human wants or needs are unlimited. They define human nature not as greedy but as the need for satisfaction of wants or needs. And that brings up the problem of limited growth while we have unlimited desires. Thus, the ideology of more and more appears. So that is one extreme. But it is based on the definition of human nature.

SK: Which involves a confused understanding of what human needs are. The problem in the West is that people see material goods as values in themselves and just seek more and more of them. One of the basic motivating factors is greed and that is the problem. As long as the West wants to focus on greed as the major economic factor, it will have problems with the Buddhist perspective.

AjB: Obviously, our raw materials are not enough for unlimited desires and unlimited growth.

LC: What is the Buddhist perspective on human needs or wants?

AjB: Just right.[13]

SK: I’d like to suggest that there are two kinds of needs: needs for the sake of survival (survival needs) and the needs of the defilements (defiled needs).

AjB: Fine, but we still must distinguish further whether it is a physical matter or a mental matter. We want a profit, but is the profit material or spiritual? This is the question. {It is natural that} we want good results or profits, but is the profit material or spiritual? Buddhism aims for the spiritual profit. Buddhism seeks spiritual satisfaction rather than material or physical gratification. Further, we should ask: Which way will create peace? Can physical gratification bring peace? Can spiritual satisfaction create peace? Or does peace require a mutual sufficiency of the two? In the end, not materialism alone, nor mentalism alone, but a mutual sufficiency between both is needed.

So there is the principle: “Do not view Buddhism as being only physical or only mental.” Buddhism is both together.

SK: For example, in religious history there are instances of people who mortify the body and of those who got carried away with meditative states. These misunderstandings result from individuals focusing solely on the mental, to the extent that they ignore the needs of the body. We can call that, “mentalism,” which is the opposite of materialism. Proper spirituality is sufficiency for both body and mind, supplying the genuine needs of both adequately.

AjB: So when both body and mind are correct, we use a new word, “Dhamma.” Something is Dhammic when both the physical and the mental factors are correct.

SK: It seems to me that this point is very important. In the West, as soon as we talk about non-material values, people will try to push us to the other extreme and discredit us as being airy-fairy or impractical. So we must make it clear that the mental extreme is also incorrect.

AjB: The meaning of “Rightness,” or “Dhamma,” includes both aspects of life. Neither pessimistic nor optimistic, it is never extreme.

SK: Which means that the mind and body are right and proper, balanced and integrated, neither being turned into an extreme. Some Buddhists get carried away, denying the reality of the body or denying that there are physical needs which leads to another extreme, one which is more Hindu than Buddhist.

AjB: Therefore, things must be right both physically and mentally. That the world will have peace merely through materialism or solely through mentalism is impossible. The world will have peace when both material and mental are correct. Spiritual wisdom integrates them. This is what we need.

LC: So avoiding extremes – the Left and the Right – that means the Middle Way, right?

SK: Of course. It’s not just a compromise, as many people try to interpret the Middle Way. “Material values are like this and Buddhist values are like that, so the Middle Way must be somewhere between the two.” Such a geometric compromise is not what is meant by the Middle Way. The Middle Way is the avoidance of all extremes.[14]

AjB: Another way to look at it is that matter and mind cannot be separated; they always go together.

SK: Separate them and you die. In fact, the Buddhist term for body and mind is actually mind-body (nāmarūpa) which is singular, not plural, thereby signifying the necessary unity of body and mind.

Currently, the worst problem is the purely material emphasis in Western economic theory. Only material things are considered, while the mind and moral values are totally forgotten. Everything is broken down into physical units: chemicals, molecules, atoms, barrels, pounds, dollars.

AjB: Nothing but matter.

LC: They call it positive science as opposed to normative science, which has value judgments.

SK: Western science doesn’t consider good and evil, or what leads to peace and what leads to violence. They think only of knowing, knowing, knowing, and of certain personal benefits. It isn’t possible to agree on all value judgments in modern society, so to maintain a facade of objectivity they just eliminate values.

AjB: Then where is peace?

SK: It is hard to find because of the difficulty in finding agreement on moral values. If we use that difficulty as an excuse to eliminate moral values, then where is there peace? Many Western theorists are abandoning the only valid means to achieve peace; as soon as moral values are eliminated, then you are saying “I do not care about this.”

AjB: For the social part to be correct, for the individual part to be correct, for the physical part to be correct and for the mental part to be correct: this is what we are looking for, so that there will be peace.

LC: Thinking like a Western social scientist, I would like to ask: How can we measure correctness?

AjB: Peace is the way to measure it.

SK: Can we say that the amount of crime, insanity, drug addiction, family breakups, etc. are also measures of correctness?

AjB: Yes. They depend on correctness or incorrectness. If correct, there won’t be such things, just peace.

SK: Things like these are the material results of human beings not living correctly. Any of these kinds of social abnormalities or human abnormalities are signs of a lack of correctness, that is, of selfishness.

AjB: There is a Thai expression which means to speak in a way that can’t be wrong: “Fist pounding the ground.” To speak pounding one’s fist on the ground means that there’s no way this statement can be wrong: What we need is no problems; peace means that there are no problems.

Nowadays, there are more and more problems. Thus, there is less and less peace. We have got the kind of development and progress that creates more problems. If we have too much material progress, then we will have many material problems. If we have too much mental development, then we will have many mental problems.

SK: It is interesting to note that vaḍḍhana, the Pāli word from which the Thai word for “development” or “progress” is derived, is neutral, although we now tend to give it a positive value. In its original meaning, this word can be positive development or negative development, good development or bad development. However, our modern mind has forgotten this fact and now assumes that any development, any progress, is good and is a value in itself.

AjB: There are English phrases we hear often: “no problem” and “all right.” These are better than just saying “no dukkha.” To say there’s “no dukkha” doesn’t sound like much to most people, but to say “no problems” is better. Because happiness has its problems and dukkha has its problems, not having any problems is the best.

So Buddhist economics must be both spiritual and physical. We also maintain that the mind leads or guides the material. So make the mind correct first, then the material will also be correct.

SK: Many people seem to believe that the material must come first. If we arrange material things properly, the mental part will be fine. Some yogis also think like this. They are very concerned with exercising the body, are scrupulous about diet, are very health conscious.

AjB: If the mind is not correct, one would walk the wrong way. No matter what you do to manage the body, you will walk the wrong way if the mind is not right. If our mental economy is correct, it will make the material economy correct.

The leadership of society must also be correct if they are going to lead the rest of society in correctness.

LC: I have been collecting modern works on modern applications of Buddhism and I have found that there has been a development of Buddhist law, Buddhist ethics, Buddhist psychology, Buddhist sociology, and Buddhist economics in the last fifteen years. I believe that monks who know Buddhist philosophy could afford many insights in these areas.

AjB: All of those things come together in the word “correct.” Everything is joined in the simple word “correct” (sammā).

SK: In the history of Europe, when there first appeared the academic subjects of political science, sociology, humanities, etc., the academics and scholars were mainly Christian monks and priests. So Leonardo is asking you if it is appropriate for Buddhist monks to help in the development of Buddhist law, ethics, psychology, etc. The monks are the ones who understand “Buddhist philosophy”[15] well, but nowadays mostly lay scholars are working on these subjects, and very few monks.

AjB: Monks can help make correctness happen. The thing in which monks can seriously help, can really help, is in helping make these things correct. Then there will be peace.

Now, the social sciences go along according to the desires and inclinations of the social scientists, so they never come together in peace. Thus, we have no peace. We need to pull all of them together and collect them in correctness for the sake of peace.

SK: The whole character or trend of modern social science is just to please the researchers themselves, and the people who pay them, rather than looking for peace.

AjB: The word “correct” is ambiguous. It can be correct in terms of other things as well. Our correctness is for peace alone, just for the sake of peace. Buddhists will be correct for the sake of Nibbāna, the highest peace.

LC: In the universities, they teach you sociology or economics but they don’t teach you Buddhist philosophy. I have been in Mahāchulalongkorn Buddhist University (Bangkok) and the monks only study Buddhist philosophy. The monks don’t study economics, sociology, or even psychotherapy. Why is one group just training in Buddhist philosophy (religious subjects) and the other group in only social sciences (worldly subjects)?

AjB: If not for the world, then it can’t be correct because the problems are of the world. Since they are the world’s problems, the monks must understand the world. Now they study in the new fields “chasing after the rear ends of the farangs,” not correctly.

SK: The secular universities in Thailand are copies of Western universities, and the monks’ universities are copies of the secular universities, so they are far from complete. There are many things lacking and out-of-balance.

AjB: To study it as philosophy using the principles of philosophy is never really Dhamma. It is just philosophy, which is a completely different word. If philosophy, it uses the reasoning of speculation. If Dhamma, it uses the reasoning of direct spiritual experience.

SK: This so-called Buddhist philosophy is merely thinking about the Buddhist teachings using logic, rational arguments, and modern critical techniques. It can never be Dhamma. It is merely philosophy.

AjB: One approach learns from hypotheses; the other approach learns from reality (or truth).

SK: I think he is suggesting that in some of these Buddhist universities the monks aren’t really learning Buddhism. They’re learning about Buddhism, but in non-Buddhist ways. It isn’t practical, so it ends up being philosophy. They use a foreign methodology that is inappropriate for the lesson.

AjB: It uses thought or the reasoning from thought rather than reality or truth, rather than the reasoning from experience. So it doesn’t relate to reality. It’s not in line with truth or with nature. It just uses thought and speculation. It must use the experience from nature, the truth from nature, directly from nature, to be correct and in line with the truth.

SK: This empirical approach is so direct that it doesn’t require any hypotheses. The Western scientific method is indirect because of its dependence on hypotheses, which can bias observation. The truly Buddhist approach is merely empirical.

AjB: The conclusions are much different when some come merely from thinking and speculation while others come from direct observation, investigation, and experience of reality, that is, from actually doing it, from learning by doing. Philosophy has no end. There’s no way it can be completed or reach a genuine conclusion. Because it’s based in speculative reasoning, the reasons come endlessly. But if we learn from Nature, we have the right to finish, to reach a satisfactory conclusion. This way has an end. To study in a philosophical way never reaches an end. It constantly sprouts and proliferates new assumptions, new questions, new hypothesis, new opinions.

SK: With the Buddhist or Dhammic approach of learning from nature – always referring to and in the terms of nature – there are certain data that repeat themselves. The field of data is constantly changing, but more or less repeating itself, so there is the possibility of finding a final conclusion.

AjB: To study Dhamma in a philosophical way is not worth the trouble. It is not practically worthwhile. To learn in a philosophical way can be a lot of fun, stimulating, and interesting, but it is not really worth the effort.

We accept that economics is for the sake of getting good results, is for making a profit. The question is what kind of profit – material or spiritual or both together?

Most foreigners categorize Buddhism as being psychological, as being about the mind. But we say, “No, it’s about both the mind and the matter.” Buddhism seeks to solve the problems of both the mental and the material. We have the term “mind-body” (nāmarūpa) which is grammatically singular. We don’t separate the two. We can only separate them in words: body and mind. In reality, the mind-body is inseparable.

Economics must be for the mind-body as a whole. And we must aim for correctness, which means “no problems.” When there are no problems, there is peace.

The United Nations talks about peace, but there’s never any peace because there’s no correctness. Rather than have a U.N.O. it would be better to have a U.R.O.[16]

Peace is hard to understand. Peace of the body is merely material peace; peace of the mind is merely mental peace. To be correct, there must be peace of both.

If you ask a small child what peace is and then ask an older person, the answers will be vastly different. If you ask the employers and then the workers what peace is, you will get different answers that will never meet.

SK: Any more questions?

LC: I’d like to thank Tan Ajahn for his help. Your teachings these two days will help me to see things more clearly.

AjB: You must be able to answer the question “What is peace?” correctly.

Leonardo Chapela: Lastly, I’d like to ask for your blessing of my work. This is a custom in the Tibetan tradition which I have been studying.

AjB: The ability to make everything correct: that is the highest blessing!

It’s funny that at one time in Thailand they taught that peace is being prepared to fight. If we aren’t ready to fight, there won’t be peace.

SK: When was that?

AjB: During Rāmā VI’s reign (1910-1925). If our soldiers are ready, that’s peace.

SK: They probably thought that Thailand could then defend itself.

AjB: Yes, they meant mainly for defense, but that isn’t peace itself. It will never create peace. The more prepared to fight, the easier it is to fight.The easier it is to fight, the less there is peace. It takes nothing to start fighting once you’re ready.

Study unselfishness, practice unselfishness, this will bring about peace.

The teaching of not-self leads to unselfishness easily. When we know that it isn’t really self or me, then it’s easy to be unselfish.

I’d like to say that the Christian cross renounces or sacrifices selfishness. The cross is a symbol of giving up selfishness. It is a tool for peace.[17] If we are to redeem ourselves, we must be unselfish. If we are to redeem the world, we must be unselfish. Unselfishness is the redemption of everything.

Now, nobody wants that. All they want is selfishness: to be selfish and to accumulate. They’re committed to being bloodsucking capitalists or parasitic capitalists. That is the greatest selfishness: to suck the blood of something until it dies, just so that one will live.

All the universities in the world study selfishness {and not in order to get rid of it}.

SK: Are the monks’ universities any different?

AjB: No different, just a little more profound and subtle. But still the same subject matter, there isn’t any other. The monks’ universities should guide the secular universities.

Santikaro Bhikkhu: Instead, they’re just chasing after or imitating them. Lay people have status because they have a “Dr.” on their names, so now all the monks want to get a “Dr.” too. It isn’t enough to be “Venerable” anymore.

Ajahn Buddhadāsa: It’s fashionable, it looks good. The old Thai word for doctor is maw, which implies cunning. {To be a “Maw This” or “Maw That,” whether medicine, spirits, crocodiles, or whatever was to be expert at it.} Then there’s the word hua maw (“head-doctor”) which is to be incredibly cunning, totally cunning, to think like a doctor. Hua maw means to be able to find loopholes in the law and exploit them. And they say that any ancient city, such as Chaiya (the local town) or Nakhon Si Thammarat (the next province to the south), has many of these “doctor heads.”

[The tape ran out. The following is reconstructed from memory.]

Lastly, I would like to mention that the economist’s attitude and approach should be that of a “spiritual farmer” who follows the principle of the seven factors of awakening (bojjhaṇga). The seven factors of awakening are mindfulness, investigation of dhammas, satisfaction, effort, tranquility, concentration, and upekkhā (looking on with equanimity).[18] Details can be found in the Ānāpānasati Sutta.[19]

These seven factors can be applied to any activity, such as, ordinary agriculture. The conservative Buddhists get upset when I say this, but a farmer needs all seven factors to plow his field. First, he must be attentive to what he is doing the whole time he is doing it. Then, he investigates what to do, how best to do it, and what knowledge should be applied. Once he is confident about what to do, he can put effort into the enterprise. Through balanced effort, happiness and satisfaction will arise. Then, the body will calm down and the mind will become tranquil. With that tranquility, the mind can stabilize itself and concentrate properly. Otherwise, he couldn’t plow a straight furrow. With even-mindedness the farmer looks on, making sure that everything goes correctly. Regularly applying these seven factors the farmer has an excellent harvest.

While plowing and harvesting are physical enterprises, there is also a spiritual enterprise. The “spiritual farmer” must use the same seven factors, but now on a higher level. First, she is attentive to the flow of events in the mind. With this mindfulness, she chooses and takes up the most appropriate Dhamma principle for each situation. Knowing what principle to practice, she arouses energy and puts effort into that practice. Through correct practice, non-sensual satisfaction and joy arise. This satisfaction has a healthy effect on the body and mind; they both calm down. Then, the mind is finally able to stabilize and focus. And with upekkhā watching over that concentrated mind, it looks deeply into the nature of the things until it understands how to make everything correct. Continuing to develop and perfect these seven factors of awakening, the spiritual farmer eventually reaps the finest harvest, the highest blessing: the ability to make everything correct.

So this is a last principle for you and your fellow economists and social scientists to consider. In addition to the material things which you study, integrate the mental or spiritual side. Then, it will be possible to make everything correct and we will have peace. That is the best blessing there is.

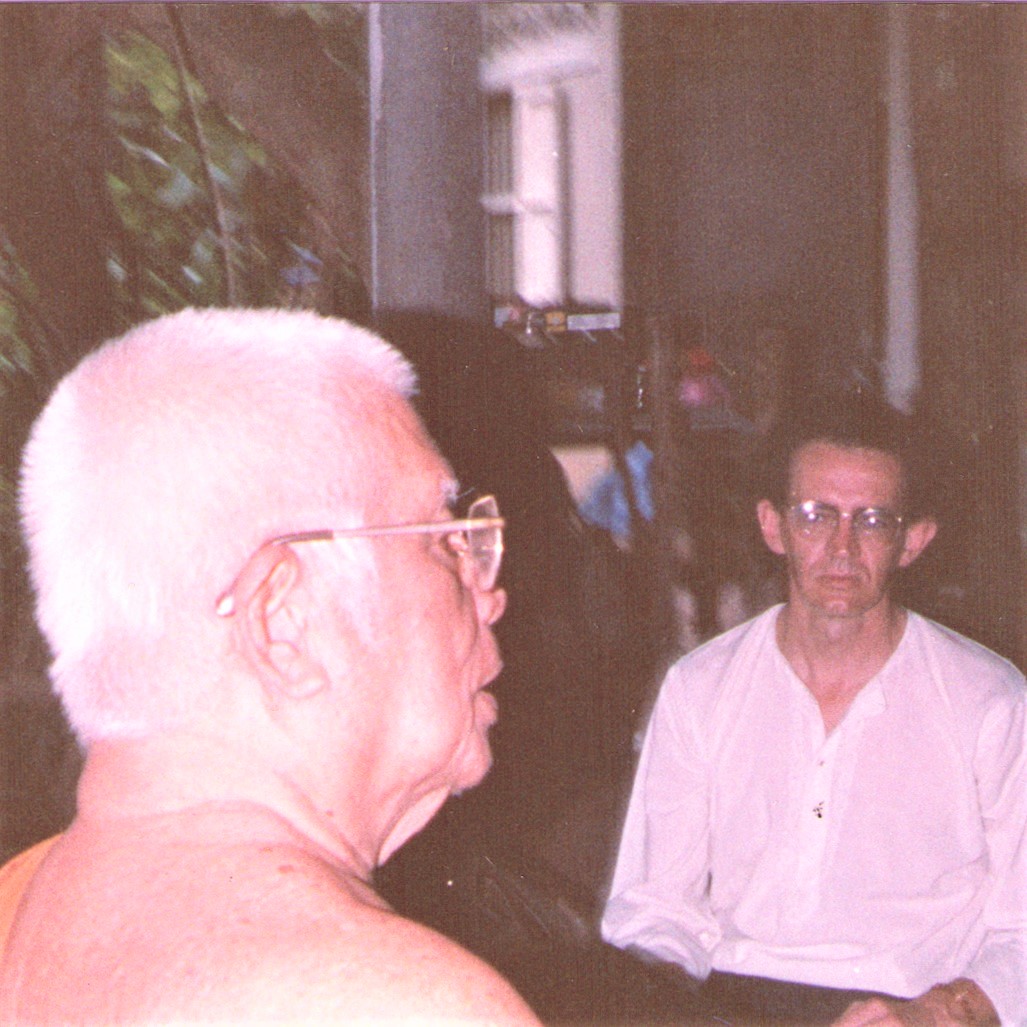

Photograph: "Leonardo Chapela with Ajahn Buddhadāsa" taken in 1991 at Suan Mokkh, from the collection of the author.

[1] The word ‘selfishness’ (in Thai, literally, ‘seeing regarding oneself,’ to care about oneself, to think in terms of oneself) appears throughout this interview and any of Tan Ajahn’s discussions of morality (sīladhamma). It should not be confused with ‘enlightened self-interest’ or ‘duty.’ Tan Ajahn will develop this distinction later in the interview.

[2] As the written questions were quite long, they were translated in summary form.

[3] The end of all greed, hatred, and delusion, of all concepts of self and egoism, thus, of all suffering (dukkha).

[4] In modern Thai, the spelling of these terms is derived from Sanskrit but they are pronounced pretty much as if spelled according to the Pāli. Here we use the more simple Pāli spelling.

[5] More precisely: “Everything is not-self.”

[6] Gentle, originally meant ‘noble, of noble birth.’ A gentleman was one of good breeding, honor, worthy ideals, and refinement of thought and action.

[7] Someone who has abandoned all ‘I’ and ‘mine,’ thus all greed, hatred, and delusion, who has realized Nibbāna and transcended all dukkha.

[8] Ānāpānasati or ‘mindfulness with breathing in and out’ is the name for a system of meditation practiced and taught by the Buddha before, during, and after the Great Awakening. While the Buddha taught it as a series of lessons or contemplations leading to liberation, it is often watered down to merely being aware of the breathing. Ānāpāna is a popular term for these simplified versions.

[9] None of the factors of the Noble Eightfold Path are correct when taken in isolation. Their correctness is in working together as a single path guided by right understanding and aiming for Nibbāna.

[10] Tan Ajahn likes to talk about the Pāli term jīvita-saṃvohāra (the business or commerce of life). This life or mind-body is our original stake or investment, lent to us by nature. If we invest wisely, we can make the best profit — Nibbāna. If we invest foolishly, all we get is dukkha, no matter how much material wealth we have.

[11] Although the term ‘Middle Way’ is widely preferred, the term ‘mean’ or ‘way of the mean,’ from the Latin, is closer to the Buddha’s meaning. While ‘mean’ (as noun) can also mean ‘middle’ or ‘intermediate,’ it has the desired meaning of ‘absence or avoidance of all extremes, moderation.’

[12] We do not mean to imply that there are no spiritual values in the West. We are speaking of the dominant trends, especially economic.

[13] The Thai word used here is paw dee. Paw means ‘enough, adequate, sufficient,’ and dee means ‘good, all right, favorable, well.’ Together they mean ‘just right, the proper amount.’

[14] ‘Middle’ here does not mean ‘between,’ rather it means ‘above and beyond,’ transcending both poles of the duality.

[15] Tan Ajahn doesn’t approve of the term ‘Buddhist philosophy.’

[16] United Religions Organization: Tan Ajahn thinks such a group would have a better chance to overcome the selfishness which dominates international bodies like the United Nations.

[17] The upright represents ‘I,’ the ego or self. The crosspiece cuts the ‘I.’

[18] The usual translations of upekkhā, ‘equanimity’ and ‘indifference,’ are not sufficient here. As concentration (samādhi) does the work of ‘seeing things as they really are,’ upekkhā looks on that concentrated mind with perfect equanimity, that is, without any bias, without being influenced by anything positive or negative that occurs.

[19] MN 118.